Michael MacConnell: Crime fiction author

Michael MacConnell has been writing crime stories in the second grade. His father loved Sherlock Holmes and watched old remakes so crime fiction has always been an influence for him.

Michael MacConnell has been writing crime stories in the second grade. His father loved Sherlock Holmes and watched old remakes so crime fiction has always been an influence for him.

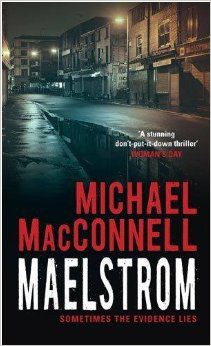

He wrote his first novel Maelstrom which was released in October 2007 and got excellent reviews. Maelstrom is a 2008 Ned Kelly nominee for Best First Novel.

His second novel Splinter was launched in July 2008. Both of his books are crime fiction.

Michael studied international relations, history and ancient history at Sydney University and was exposed to diplomats.

He went into law enforcement, worked on doors at nightclubs, did corporate security work and worked at RailCorp as a transit officer.

Click play to listen. Running time: 31.52

Transcript

* Please note that these transcripts have been edited for readability

Valerie:

Michael, thank you for joining us today.

Michael:

That's perfectly all right.

Valerie:

Tell us, why did you start getting into crime fiction specifically?

Michael:

I think originally it was because of three reasons. First off, because I was really drawn to this sense of atmosphere that you get uniquely from a crime novel, or from the really good crime novels that are out there. I started reading novelists like Lee Child and Dean Koontz and Robert Ellis and so forth, and I loved the way they drew you into the worlds that they had created. The sense of atmosphere it was really palpable; not always dark but always textured and always very tangible and you could really sense it and you really put yourself into it.

Second was flexibility of novels, I really love the way, especially, especially with Lee Child I think more than any other crime writer than I can think of, he was able to work into his novels such a broad scope. Especially in his Jack Reacher series, he was able to work such a broad scope of stories and ideas and characters into that series. One was like the other in some ways, the same thing that made you enjoy one book kept you coming back for more but there was always that sense that something completely different could happen in this novel.

And then finally, realism, I think, especially for myself and for a lot of people crime fiction is more accessible than perhaps some other types of fiction because it's so realistic. You can see the things happening that happen in a crime novel perhaps more than you could in say something like speculative fiction, which is a fantastic genre but it's a little bit easier to see somebody kidnapping someone else than somebody suddenly sprouting two heads and speaking Martian.

Valerie:

Sure.

Michael:

That's why anyway. That's why I enjoy it.

Valerie:

Would you say you've got an overactive imagination or an obsession with all things criminal? I'm assuming you might have to have that in crime writing?

Michael:

Yes, definitely. I've always had that, I've always been – it wasn't of great benefit to me in high school. I've always been a daydreamer. I've always been somebody who really enjoys getting caught up in an idea, in a concept and really just playing it out in my mind. I think over time as I actually got seriously into writing as opposed to just as a hobby, I think that was really important for the evolution of the story lines, for realism, and especially for coherency of characters; especially for that.

I had to believe these characters were real and they had to be real to me if they were going to have that coherent sense, if they were always going to be consistent to themselves. So I think it's definitely a requirement for crime writing.

Valerie:

You say you have to believe your characters are real, and one of your main characters is a woman, Sarah Reilly. Is it hard writing about a woman?

Michael:

I get this a lot. No, no, surprisingly not. When Sarah was born so to speak it was a very easy transition from pure fantasy into a quasi-realistic existence in my mind. No, she was very easy to write from. I had met an FBI agent, a very famous FBI agent in the United States by the name of Candace DeLong. She had written her memoirs after I think it was about 15 or 20 years in the FBI and she's very similar to the character that I've invented in Sarah. She isn't exactly the same but it certainly made it a lot easier meeting this person and sort of saying to myself, “These people really do exist. They're out there. These women who will kick down doors, jump through and arrest serial killers. They're out there.” And, she did it on multiple occasions.

It really wasn't that hard, in the case of Sarah. I think if you asked me tomorrow to come up with a new female character just at the drop of a hat, I think it would take a little bit of time. It took a little bit longer to come up with Sarah's new partner in the second novel in the series Splinter. It took a little bit of time to come up with her new partner, which was a female character. In Sarah's case it was easy. In any other case I think it would be more of a process.

Valerie:

How did you meet Candace?

Michael:

I was in the United States and she was doing a book signing at, I think it was Barnes & Noble, and it was sort of a disappointing situation I think for her because there weren't very many people there. It was in Kansas. There weren't too many – there were about five or six people who were lined up and I deliberately waited till the end, and as one person came in I'd let them in front of me so I would be the last person there. And then when I was the last person there, I basically just pitted her with questions and bothered her and spoke to her. She was very kind and very generous with her time and with her stories and so on. So that was fantastic.

Valerie:

When did you actually start thinking, “I want to be a writer?” When did that occur to you that that's something that you really wanted to pursue?

Michael:

I think probably sometime around 7th or 8th grade where I had a huge crush on a girl by the name of Melissa McKay in high school and I used to write her these epic love letters.

Valerie:

Oh my God.

Michael:

We're talking epistles, we're talking pure missives of absolute devotion.

Yeah I basically found that I enjoyed the act of writing. From doing that I found that I actually enjoyed the art of converting ideas and thoughts into the written word basically. And as a result I just started writing stories.

Originally it was just for myself and it wasn't really for anybody else. I really enjoyed a lot of science fiction at that time and as science fiction sort of lends itself to short story writing, I did quite a few of those. And like I say, originally it was just for myself, my family, a few friends might have read it but it wasn't really something that I took seriously for a very, very long time.

Valerie:

Then as an adult when did you decide to make a go of it and actually start writing your first novel?

Michael:

It wasn't really a single point where it changed over. I think when it became something that I took more seriously was definitely when a friend of mine met Selwa Anthony who is my literary agent at a wedding of all places. This is a very good friend and she basically agreed after much lobbying to read this manuscript. And when I submitted it to her, I really didn't think there was much chance of being accepted because Selwa was pretty major as agents go. She's pretty much the number one agent in Australia.

When she wrote back and she said that yes she was interested in working on the manuscript and working with me, then I think that was the point at which I thought, “This is not just a hobby anymore. This is something I can actually pursue.”

Valerie:

I have to ask, what happened with Melissa McKay? Did she enjoy getting your letters?

Michael:

I don't think so because she broke up with me. I think maybe I wrote to her too much or something.That didn't work out unfortunately.

Valerie:

In Maelstrom you have a character, the Violet-Eyed Man. Is that based on a real person at all or how did you come up with that character?

Michael:

Yes, that is. Basically the character of Bill Gunther is based more or less on a real serial killer by the name of Dennis Rader who is more commonly known in the United States as the BTK Killer who would bind, torture, kill, killer. Not a terribly nice fellow. He was unusual in the sense that for an extensive period of time, a number of years, he actually managed to conquer his desire to kill people. He had set out as a young man to do these serial killings as incredibly, he is cruel, sadistic killings. At some point after a couple of years he just stopped and he stopped for approximately I think it was about 15 years, 15 to 20 years. It was a significant period of time.

And then for some reason, I can't remember exactly what it was, he started again. He started doing the same thing and he started contacting the authorities and taunting them with the fact that he had managed to get away. And it turned out to be a very bad idea for him because he really wasn't up on the way that computer technology had enhanced and computer forensics had advanced, and they were able to find him in that way.

But I was really impressed, well impressed is not the right word, I was intrigued by the way he was so in control of his pathology, his driving motivation to kill. He did master it for a very long time and I thought really that made him even more of a frightening serial killer because he wasn't driven by it. He wasn't going to, for a while there anyway, lose control in a way that would allow law enforcement to more easily track and capture him . This was the kind of fellow who had the kind of mentality who could become a very serious problem for law enforcement if he had backed up that control with a little bit of knowledge.

. This was the kind of fellow who had the kind of mentality who could become a very serious problem for law enforcement if he had backed up that control with a little bit of knowledge.

So really all I did was I just took the character of Dennis Rader and I made him a little bit worse in the sense that my character took the idea of killing more seriously. He had come up with a method by which he could kill an infinite number of people and never be caught, never even be known, never be detected. So it was just a matter of equipping that character with the tangible knowledge that could very easily have been acquired by a plethora of true crime novels and forensic texts that are available.

Valerie:

With crime fiction and particularly Maelstrom has lots of plot twists and lots of turns. When you're writing do you plot it out somehow organisationally on a wall or how do you actually keep track and make sure it all fits in?

Michael:

I have very patient editors in Vanessa Radnidge of Hachette and Selwa Anthony, which is the firewall that prevents inconsistencies, mistakes and errors getting through. But in the beginning it's a combination of planning and spontaneity as well. I think if you're going to write something that is going to strike the reader as being spontaneous, then you have to be a little bit spontaneous with yourself.

You can only plot so much and then when you're in the act of writing it and fleshing it out and making it a real or quasi-real event in your mind anyway, I think things occur to you that before wouldn't have occurred to you, “Well I could do this instead of that,” and that's really unexpected. But it still follows more or less the same flow of the story that you had plotted out I think that makes it a little bit more interesting, a little bit more enjoyable and the credibility comes in going back over it and reading it and making sure.

Because you can get so close to it, obviously you can get so close to what you're writing that you completely lose track of where you are and how realistic it really is. So I think taking a step back a little bit at a time and then going through it and reading it and making sure that it flows I think is really important.

Valerie:

What do you typically start with in your head as the idea? The crime or the ending or a particular plot or what's the first thing that starts germinating in your brain?

Michael:

The villain, always the villain. In the case of Maelstrom I came up with the idea when I was sitting down one night and I was thinking to myself, “What would be the perfect serial killer?”

Valerie:

Of course, as you do when you're sitting down at night.

Michael:

I had just finished reading a novel. I can't remember which one it was but it was really good and I was really impressed by the antagonist. I can't remember which one it was. But I did get to the point I started thinking to myself, “The serial killers are the perfect antagonist in any book. They're characters, they can't really be reasoned with, they can't be to an extent completely understood, they can't be mapped out, they can't be predicted.” They have the elements of the professional and the amateur blended into their modus operandi of the way they do things. So it makes them incredibly, incredibly dangerous.

I was thinking about writing a crime novel but I didn't really know what to anchor it on. I just started toying with the idea of what would is or what would be or what could be the perfect serial killer. And it's a deceptive question because once you start thinking about that you think to yourself, “How do you define one? Is it a matter of body count or is it a matter of remaining undetected?” Eventually I reached the conclusion that it was a matter of remaining undetected, the ability to do what they do without being detected or even known.

Then I really had to go about deciding, how is he going to do this? How is he going to do something that technically would be impossible? I basically just immersed myself in forensic studies. I spoke to FBI agents at the Public Affairs Office in Washington, and basically just went about piecing together this villain, this character. And I got a big break with reading about Dennis Rader but after that I really had to equip him with a number of other facets of his personality. For instance, a lot of the serial killers bring themselves undone because they need to kill in a particular way to gain a certain degree of satisfaction.

In the case of Bill Gunther, I thought it would be much better if he was far more simple in the sense that he just liked to see things die, he just liked to see people die and it didn't really matter how they died. That in itself is very deceptive because it seems so simple but at the same time it empowers him immensely because forensic analysts to a huge degree rely upon these killers following a pattern in order to track them, in order to map out their personalities, they would study the victimology, they would start with the target rather than with the killer himself, but in order to understand the killer.

If a killer went about killing anyone he pleased in any manner that he chose, he would be extremely difficult if not impossible to understand him, to track him and to catch him. So really I started with the villains. It was the same way in Splinter. I really wanted to come up with a character that would not just be my protagonist or Reilly's equal but actually a little bit better than her, a bit smarter than her, a little bit more cunning, a little bit more ruthless than she is. I wanted to set up a one-on-one encounter that couldn't effectively be on in the conventional sense. I wanted it to end in a way that wasn't conventional, that was a little bit more like real life. It was really just a matter of constructing the villains. That's where it started.

Valerie:

When you construct the villains and do all this research into their psychology and as you say forensics, does that kind of fill your head with all sorts of stuff? Does it kind of muck around with your daily thoughts?

Michael:

Yes, actually it's not very pleasant. I took a break after writing Maelstrom for a number of months where I didn't actually want to write about crime stuff, because even though I did work in law enforcement writing about serial killers and thinking about these things and analysing these things and trying to understand these things is different to anything that I'd done before. And, as a result it's a little bit depressing because when you think that there really are these people out there who derive pleasure from destroying a human being and they have no regard whatsoever for the repercussions of that act. They only concentrate and focus completely upon the enjoyment that they derive from it and it's incredibly upsetting. It's incredibly saddening to know that we aren't quite advanced enough as a species that we can't get away from that kind of reasonless brutality.

Valerie:

How do you cope with that?

Michael:

I read generally other things. I will go up and watch a comedy movie on TV, I'll go upstairs and do that. I'll go play with our dog or with our cat or I'll go out with my wife and I'll spend too much at the bookstore, as you do. I just try to get away from that altogether and I compartmentalise it a lot too.

When I start thinking about it, I get a good idea, a good grocery list of the things that I want to do, I set about going about doing it, I finish it off, I finish the edits off and it's done and that's it. And I literally never go back. I've never opened up a copy of Maelstrom or Splinter and actually looked at it.

Valerie:

Oh really?

Michael:

I've never done it.

Valerie:

Wow.

Michael:

It's really just a matter of doing it and then moving on to our next project.

Valerie:

How long after Maelstrom did you write Splinter and when you wrote Maelstrom did you realise there was a second book with Sarah in it?

Michael:

I actually got a two-book deal with Hachette that called for a specific timetable of work to be completed. So it was really a matter of months. It was a matter of months after writing Maelstrom that I started and completed very quickly. And Maelstrom took a long time to write, Maelstrom took I couldn't honestly say probably about 18 months to two years in total to write because I really didn't know what I was doing. But Splinter was much faster. I actually had a good idea by then of what I was doing and what it took to actually go about compiling a book and setting out and writing it.

Valerie:

How long did that take to write?

Michael:

About three months. It was very quick. It really wasn't that long at all. Maybe a little bit longer with edits; maybe about four months in total but certainly no longer than that.

Valerie:

You said you worked in law enforcement. Can you tell us a little bit about what you've done?

Michael:

Yes, sure. I started out in private security. I was working in corporate security for a while and whilst I lived in the United States with my wife I did a number of security jobs over there, everything from nightclub work on the door to a little bit of corporate work to a little bit of private investigation work. It's much easier over there because they don't have quite as strict licensing, which is not such a good thing. But it was easier for me at the time while I was over there.

When I came back here, mainly corporate stuff. I worked for a number of hotels and that sort of thing and then I was transit officer for a while. I went to work for RailCorp and worked on the trains in Sydney. That was a very enjoyable job and eye opening in a number of ways especially for exposure to criminals, a lot, a lot of exposure to criminals. There was a good reason why the New South Wales police didn't want to effectively police the railway system in New South Wales anymore. It's because it's a difficult job and just dealing with the whole range of offenders, everything from minor assaults to rapes, sexual assaults, you name it, you know malicious damage, everything.

It was just a matter of sort of going with that and dealing with that and doing that. It was a wonderful job and a wonderful experience. It really was.

Valerie:

Have you drawn much from your work in law enforcement and security for your books?

Michael:

Definitely. Especially in constructing villains I think. The thing about people who have made crime their living so to speak, there are two very distinct types of people. There are the amateurs, the enthusiastic amateurs, people who are actually more of a problem than professional criminals because they're not very predictable in the way that they act and the way that they deal with you. They're spontaneous and very emotional. You're far more likely in a situation when you're dealing with an offender who isn't a professional criminal to get into a hands-on situation and actually have to arrest them and cuff them and get into a physical confrontation than with a professional criminal.

When I worked out West, especially out around Bankstown, Parramatta and Blacktown and so on, you very quickly understood that dealing with people who were exposed to the law enforcement system would be far more cooperative; always. Especially with guys who would have met – they would always do it, they would always admit very quickly that they'd just gotten out of jail or they'd been in jail or they had a police record, that sort of thing. They would always be far more cooperative because they knew the repercussions of not being cooperative, and they really weren't interested in any dramas.

It was a job to them. It wasn't personal. It wasn't something that they would get wrapped up in emotionally. They would be calm, they would be collected, whether you caught them spraying graffiti somewhere or beating someone up, nine times out of 10 the professional criminal would just say, “Okay. Where are we off to?” And that was it. It was helpful in constructing the mentality of a criminal and the way that they deal with law enforcement. It was very helpful in that regard, definitely.

Valerie:

When you are writing, tell me about your typical working day? Are you writing your next novel now?

Michael:

Yes, I am actually. I'm working on a couple of projects at once. I don't know if there is a typical working day though, I really don't. When you start writing full time, it becomes a matter of you become your own task master obviously and you have to set your own goals and you have to keep to them every single day. I actually find ironically that everyone thinks it would be wonderful to write full time and that's a goal for a lot of people. It was certainly a goal for me for a long time because you think it will be so much easier.

The reality for me is that I work probably about three or four hours longer now than I ever did in a full time job, without a doubt, because I get up, I get my breakfast and I've already started, you know. And, I will work – on a typical day I'll probably stop around about the time that my wife finishes work. Other days I'll just work straight through. I can work straight through till about 12 at night or something like that.

Valerie:

Wow.

Michael:

Yes. I'll generate something like 10,000 words of text, 10,000 or 12,000 words of text.

Valerie:

A day?

Michael:

Yes, I can. It's not all good text. It's not all good, a lot of it ends up on the cutting room floor but no, I've never had a problem with that. I can honestly say I've never had writer's block. I've never been short for something to say.

Valerie:

That's great. Finally then, what advice would you give to people who want to do exactly what you're doing, become writers?

Michael:

I think they could avoid the same mistake I made and they could save themselves a lot of time if they could realise very early on that this is something they would like to pursue seriously and to be serious about it. It really is just a matter of, I mean there is a certain amount of luck involved but if you know the market and if you know stories and you know what you enjoy and you can look at the market and say, “Okay, I see what's out there but more importantly I see what isn't out there.” If you can do that and then go through the process of actually learning how to write a book very quickly and then study the process of getting representation, getting published, understanding publicity and that sort of thing and actually taking active steps every day, just small little ordinary things, to make it more likely that that will happen, then the chances of getting published and doing something serious with their writing it cascades and it becomes a catalyst for real success, actual success.

If they do that, if they go out of their way to meet people in the industry, go to book signings, go to industry parties, to book launches and speak to people. People are always very happy to speak to you. Some of the most approachable people in the world work in publishing, be they agents or publishers or editors, are fantastically nice people. Really it's just a matter of a person increasing their own chances, as Sun Tzu said, “Cast a wide net.” You do that, you increase your chances hugely.

Valerie:

Wonderful. Thank you for your advice and thank you for your time today Michael.

Michael:

Not at all. It was a great pleasure.

Browse posts by category

- Categories: Uncategorized